In those long-ago, far-away, now-otherworldly-seeming days between Christmas and the Eaton Fire, I met Pasadena-based playwright Soji Kashiwagi for a cup of tea at Callisto Tea House, which just re-opened in time for Lunar New Year and Valentine’s Day pourings, and of course the Day of Remembrance on February 19th.

He’s the founder of the Grateful Crane Ensemble and has written and produced numerous theatrical pieces about life in the Japanese American incarceration camps, among them “The Camp Dance: The Music and The Memories,” and the comedy-drama “Garage Door Opener” — a work that Kashiwagi has subtitled “A Japanese American Dysfunctional Play,” a phrase that never fails to summon laughter from packed houses.

Bay area-born Kashiwagi is Sansei, meaning third generation Japanese American, born outside of Japan with at least one Nisei parent. The Nisei are second generation, born outside of Japan, with at least one Issei or Japan-born parent.

His plays, he says “…have a very visceral effect. The practice of gaman, you know, of enduring the unendurable, well, all of that emotion has to get out somehow, and the outburst of laughing and crying can be very healing, especially for Nisei, who tend to be quite reserved.” Kashiwagi adds that Buddhist churches now take particular interest in his work.

Roots of Resistance

The appeal of the stories reaches beyond culture, BTW. Non-Asians can relate to the story of Glenn and Sharon Tanaka, fictional siblings in “Garage Door Opener” who must sift through a garageful of empty, carefully washed tofu containers and “good” rubber bands collected from broccoli stalks after their thrifty parents have died. Kashiwagi uses the Japanese phrase “mottai-nai” — “don’t be wasteful.”

“This idea of unpacking really resonates,” he says. “It’s not just the literal divesting of stuff. It’s the lifelong process of sorting out what things mean, and understanding what has been passed on.”

To mark the Day of Remembrance in 2024, Kashiwagi spoke about his experience as the “Son of a No-No Boy.”

He says, “My parents, Hiroshi and Sadako Kashiwagi, were forcibly removed from their homes in the Sacramento area, and taken to the assembly center…” — he makes air-quotes here — “…in Marysville (California) first, and then moved to Tule Lake which later became the segregated ‘No-No’ camp…” (more air-quotes) “…for disloyal…” (air-quotes) “…Japanese Americans. My dad passed away in 2019. He became a reluctant face of the No-No’s and spent many years speaking out about his experience at Tule Lake as a playwright, poet, author, actor and activist.”

The sticking-point in Hiroshi’s camp experience had to do with the so-called Loyalty Questionnaire, a series of questions posed by the War Relocation Authority and the War Department to Japanese Americans in 1943 while they were incarcerated, in part as a screening exercise for potential military recruits.

Questions 27 and 28 drew the proverbial line in the sand, as explained by the Densho Encyclopedia:

“Question number 27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as serving in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. Question number 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Both questions caused a great deal of concern and unrest. Citizens resented being asked to renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan when they had never held a loyalty to the Emperor. Japanese immigrants were barred from becoming U.S. citizens on the basis of racial exclusion, so renouncing their only citizenship would be problematic. Young men worried that declaring their willingness to serve in combat units of the army would be akin to volunteering.”

Given the iconic self-control that is a keystone of traditional Japanese culture — what Kashiwagi calls “the Samurai warrior-code of sucking it up” — the entire issue of protest and of opposing authority is fraught.

“Americans today are much more comfortable taking a knee, pushing back against the establishment,” he says. “My dad’s attitude was, ‘I’m already loyal,’ so he voted No and No on Questions 27 and 28. Sitting in camp, he found the whole thing extremely insulting.”

The No-No Boys, he says, were stigmatized as troublemakers. “Veterans were praised. The No-Nos were judged and shunned within our community as cowards.” Although the remaining Issei and Nisei generally discuss their camp experience in detached terms, it is an error of perception to believe that the Japanese American inmates went quietly to their destiny. For example, in the autumn of 1943, based on responses to the questionnaire, the “disloyal” from various camps were sent to Tule Lake, which erupted into a mass uprising on November 4th.

By 1944, tensions peaked. At the center of the conflict, and not for the first time, was the case of Fred Korematsu. Korematsu was arrested in 1942 for his refusal to report to a relocation center, in spite of the fact that his parents had surrendered their home and flower-nursery business in order to comply.

The 23-year-old Fred had cosmetic surgery to alter the appearance of his eyes, and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian descent. On December 18, 1944, the United States Supreme Court upheld Korematsu’s conviction, a decision which effectively upheld the constitutionality of the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the west coast.

That same week, the announcement that Tule Lake would be closed led to more upheaval. By spring of 1945, 5,589 Japanese American citizens renounced their citizenship, many returning to a Japan they had never known.

An archival video of Soji’s father Hiroshi recounts what happened at Tule Lake. “Some young men refused to register, and asked for repatriation,” says the elder Kashiwagi. “Then the Army arrived and we were loaded at bayonet-point into trucks, taken to county jail. I remember it very vividly. All the mess-bells were all ringing. Then all of the men who had requested repatriation got into the trucks. It was very dramatic. Everyone was pretty worked up.”

The judgment against Korematsu held in place until 1983, when his conviction was overturned in the same San Francisco courthouse where Korematsu had been tried decades earlier.

In addition to the principle of gaman, Kashiwagi explains that “shikata-ga nai” — “It can’t be helped” — was commonly repeated in camp to steady morale. He likens the maxim to the traditional Daruma doll, which pops back to its upright position when tipped or tilted over.

Exile in the Wasteland

“Music was so important to them,” he recalls. “My mother really loved that song ‘Accentuate the Positive.’ So it’s no surprise that Korematsu and the No-No Boys were considered shameful, a disgrace to all Japanese. I just know, when I look at the photos of those camps, so desolate, when the temperatures would go from 30F at night to 120F at noon, I feel like, did they really hate us that much, so much that we had to be caged up out there in that wasteland?”

He points out that anti-Japanese racism flourished in America long before “Kates” (Nakajima B5N carrier-based torpedo bombers), “Vals” (Aichi D3A carrier-based dive bombers) and the formidable “Zeroes” (low-wing, all-metal carrier-based fighter monoplanes) rained destruction upon Pearl Harbor.

Known as the “Yellow Peril” circa 1906, anti-Japanese organizations formed, including the California Farm Bureau and the Japanese Exclusion League of California.

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 was specifically create to prevent land ownership among Japanese residing in the Golden State, and was not overturned by the Supreme Court until 1948 (State of California v. Oyama).

Generalized anti-Asian xenophobia portraying Asians as sub-human was easily retooled into specifically anti-Japanese sentiment, producing some of history’s most vicious racist propaganda which persisted long after the war had ended. Disney, Warner Brothers’ “Looney Tunes,” and even Dr. Seuss contributed to images we now cannot un-see.

Executive Order 9066 remained in place until then-President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9742 on June 25th, 1946. EO 9742 ordered the liquidation of the War Relocation Authority and allowed Japanese Americans to return to their homes.

But many of the newly released inmates returned home to find their belongings stolen and their property sold. Thousands of Japanese Americans lost their homes and businesses due to “failure to pay taxes,” impossible when imprisoned and any financial assets were frozen.

“Apart from the cash pay-out, the letter of apology from former President George H. W. Bush meant more. But to this day, there is no real reconciliation,” says Kashiwagi as we share the last crumbs of a chocolate chip cookie. He describes the pain felt by his mother, Sadako, about the Tule Lake cemetery being removed when the property was annexed by the National Park Service.

“At the very least, she feels that there needs to be an obelisk, a monument, something,” said Kashiwagi.

“Our mantra has changed,” he continues. “We used to say, ‘Never again.’ But now we see that ‘Never again’ is now, with what’s happening in this country. The discussion of migrant camps and separating children from their families sends shivers down a lot of Japanese American spines, and lots of other spines as well.”

By phone, we recently chatted with the extraordinary David “Mas” Masumoto, a Fresno-area organic farmer, author and activist. Among his many books, “Secret Harvests: A Hidden Story of Separation and the Resilience of a Family Farm,” illustrated by Patricia Wakida, was published by Pasadena’s Red Hen Press in 2023.

In those pages, Masumoto writes “We are bonded by a shared baggage of history we cannot escape; many will press on and carry this burden. We have an attachment to the dreams of our immigrant parents and grandparents yet sense they are destined to be broken.”

The narrative describes Baachan Masumoto, his father’s Issei mother, as “quiet and reserved,” with biceps bulging from her tiny four foot, six inch frame, the evidence of a lifetime of farm work.

Once a year, grandma exploded. Masumoto says “She had classic PTSD, wailing, crying, stomping her feet. She often fell to the floor, beating the surface with her clenched fists, shaking her head back and forth. A spasm, a fit of anger, like a tantrum and seizure, an outburst and convulsion. She would rant about how it was wrong, and my dad and my aunt would try to calm her down. Those were the only times my dad would touch grandma.”

Masumoto, who is Sansei, says he was angrier as a younger man. “I related to my father,” he says, “who, when he got the notice about all Japanese Americans having to leave, got so mad that he smashed and burned all his grapes and raisins that were ripe for harvest. But he had never talked about it. We never talked about it. I didn’t know about it until decades later when he and I were clearing out some brush on our farm, gathering up and burning some dead branches.”

Silence, he says, is not nothing.

Stories, he says, are not always told with words. “Especially when you’re Japanese, especially when you’re from the older generation,” he says. “Americans are verbose. And, now we’re living in this social media age of TMI and oversharing. This is all so un-Japanese. A lot of story is told, and held, in silence.”

Silence, he says, is not nothing. “It’s weighted, and very expressive, in Japanese tradition. Many people in the camps were from rural areas, and within that cultural frame, silence is very powerful. When you ask someone from that framework how they feel, and they are silent, they are not ignoring the question.”

Objects and artifacts take on tremendous meaning in this silence. Masumoto recalls the subject of religion being the tipping-point for many, with Buddhist families fearing specific persecution on the basis of their spiritual lives.

In contemporary times, at least two of the so-called “desert faiths,” Judaism and Christianity, coexist peacefully with Buddhist practice since Buddha is not considered a god, nor the son of a god, but is rather a revered teacher who made no claim over creation or humanity.

However, prior to the tie-dyed, electric Kool-Aid acid-tested waves of the 1960s, bringing with them the cross-cultural studies of Alan Watts et al, this understanding was not widely shared.

“The silence can be very heavy. But sometimes people understand. Armenian neighbors of my uncle saved the wooden altar (or butsudan) that he built and had in his home. They were Christians, and they understood,” says Masumoto.

We also caught up by phone with Fresno-area artist / activist Patricia Miye Wakida, who illustrated “Secret Harvests” with her evocative woodcut prints. Wakida is Yonsei (fourth generation Japanese American) whose parents were incarcerated as children in the Jerome (Arkansas) and Gila River (Arizona) camps.

Wakida says, “A lot of people still don’t want to talk about it,” “it” being the legacy of racism against Japanese Americans. “The contradictions are truly harsh. For instance, Buddhist priests were especially suspect and were persecuted. And on the other hand, we have the fact that Japanese American fighting men, obviously fighting for the USA, were among the most decorated combat units in the European Theater.” She cites Duncan Ryūken Williams’ landmark book, “American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War” as a touchstone.

For example, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated Japanese American unit, was activated by FDR on February 1st, 1943, nearly one year after the signing of EO 9066.

Composed mostly of Hawaiian-born Nisei, their motto was “Go for Broke.” The 18,000 or so fighting men earned more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, 4,000 Bronze Stars, 560 Silver Stars, 21 Medals of Honor and seven Presidential Unit Citations.

Wakida continues to actively support the work of author Williams, incidentally a Soto Zen Buddhist priest, who is the director for the Irei Project. “This project serves as a national monument to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans,” she says. “The purpose is to address the attempted erasure of those individuals of Japanese ancestry who experienced wartime incarceration by memorializing their names.” Williams serves as Irei Monument Director, and as the USC Shinso Ito Center’s director.

Repairing America’s Racial Karma

The massive, three-tiered project is referred to as the sacred book of names (Ireichō), which forms the basis for the interactive and searchable Web site archival monument (Ireizō), and light-sculpture monuments (Ireihi) which will be developed in collaboration with the Japanese American National Museum and a creative team of artists, architects and designers for installations in the camp sites of Amache, Jerome, Heart Mountain, Manzanar, Minidoka, Poston, Rohwer and Tule Lake beginning in 2026.

Wakida explains “This project was conceived to repair the racial karma of America.” The inspiration is called Kakochō, literally translating to “The Book of the Past,” a book of names typically placed on a Buddhist temple altar. “Prior attempts at memorializing the thousands of people affected by this experience have treated them as a generalized community. Our goal is to list out every name in this actual bound book that’s now traveling around the country, and then to have each of the names acknowledged by having someone stamp, meaning the small circular stamp called ‘hanko‘ in Japanese, below the line where each name is displayed.”

Wakida says that 125,284 individual names, all arranged by birth date, have been researched and bound into the Ireichō, with 81,000 of the names having already been stamped in acknowledgment.

As part of the exhibition, soil from each of the 10 incarceration camp sites has been collected and mounted into the installation, surrounded by 75 “sotoba” (wooden grave-site markers) bearing the names of America’s incarceration camps and related sites.

Via Zoom, we connected with Dr. Donna Nagata, Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan who is known for her studies on psychosocial consequences of the incarceration and historical trauma.

Nisei that Nagata interviewed 50 years after the war ended described negative emotions from their incarceration such as fear, worry, and shock. However, specific recollections varied by age. Those who were children while incarcerated also recalled camp as an “adventure.”

“For those Nisei who were in camp at a young age,” noted Nagata, “it is important to remember the heroic efforts their parents made to provide some sense of security and continuity over time, in spite of the tremendously disrupted and oppressive circumstances.”

Nagata’s work centers on intergenerational legacies of the incarceration. For her most current study, Dr. Nagata focuses upon the impacts of the camp experience among the grandchildren of the incarcerated Nisei. More than 400 Yonsei responded to open-ended online survey questions asking them to describe how the incarceration has affected their lives.

Their answers produced compelling findings, highlighting Yonsei sadness and anger from losing connection with Japanese culture and identity as the result of pressure to assimilate into mainstream American society following the war.

Nagata’s research also reveals that “Trauma sometimes can build strength and pride in the connection with those who came before you.” In response to a heritage of incarceration injustice, many Yonsei now embrace the practice of advocacy, not only to educate others about the travesty of the Japanese American war experience but also to speak out for the civil liberties of all Americans and people worldwide, in the interest of preventing similar racially based violations of human rights from occurring.

According to Nagata, some focus their educational and professional goals on the incarceration — an example would be entering public interest law — while others may reclaim their ethnic identity by learning the Japanese language or attending pilgrimages to former camp sites.

In general, the surveyed Yonsei often commented upon “family silence” about the war years, and some reported anxiety and depression among their grandparents, parents and themselves. This silence may be the mapping of interior landscapes which were walled off decades ago, and thus re-engaging with the camp experience constitutes the reconstruction of suppressed memory.

Skepticism about the federal government can also color some Yonsei attitudes. Some of the survey participants expressed “wariness” about the commitment of the current US administration to address racism and protect the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans, based upon their own families’ past.

Many Nisei, the few that are left, did not celebrate the Day of Remembrance until their children and grandchildren began asking questions. The desire to assimilate, paired with the deep calling to preserve family dignity, had pushed those conflicting memories of barbed-wire and boogie-woogie into the deepest recesses of forgetting, or at least into the vault of not speaking.

June Berk did not take to the streets to make her rage and grief known. Instead, she put on lipstick and, smiling, walked out into the often-hostile world, proving that resistance may take many forms.

David “Mas” Masumoto speaks with the patience that only farmers know. As Southern Californians were recently reminded, wind and fire will have their way with us. So will earthquake and tsunami, bird flu and overpriced eggs. Masumoto views these challenges as opportunities to grow.

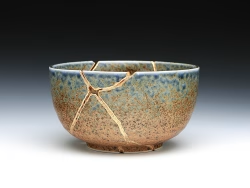

The analogy of kintsugi – repairing broken vessels with gold dust – may be a bit lofty for this son of the soil who seems most at home with fresh dirt under his fingernails. His numerous books about growing on the land are devoid of showy heroics.

Instead, Masumoto writes about what it takes to press on in the face of persistent racial discrimination and other challenges, mirroring the silent, slow, steady determination of the seed to split and germinate, the perseverance of the seedling pushing its way up toward the light, the endurance of young trees to survive pests, drought, and other whims of the gods.

We talked about this on the phone. “With stone fruit, like our famous Sun Crest peaches, I look at them kind of like my family, our people. We find that if you stress them a little before harvest, it actually brings out the best in the fruit. The plant-intelligence picks up on the fact that its life is in danger, and that it better flower and reproduce fast, or else there goes the neighborhood. The trees that are too cultivated, too babied, they don’t do as well. But stressing the peach trees makes them produce more sugar, so fragrant and sweet.”

“I wonder if our grandparents knew this, somehow,” Masumoto said.